RESEARCH

Research in our Lab reveals how photosynthetic fluxes interact with plant metabolism and the environment to drive energy capture, carbon fixation and growth.

We use these findings to scale up the impact of photosynthetic metabolism to the leaf and canopy scale. Questions we find particularly interesting are those that produce a quantitative or integrative result. Our long-term vision is to combine classical measurements of carbon and energy exchange with recent advances in resolving metabolic fluxes through metabolism using isotopic labeling methods. Our ultimate goal is to engineer more efficient photosynthesis under dynamic conditions and better understand our planet’s response to climate change.

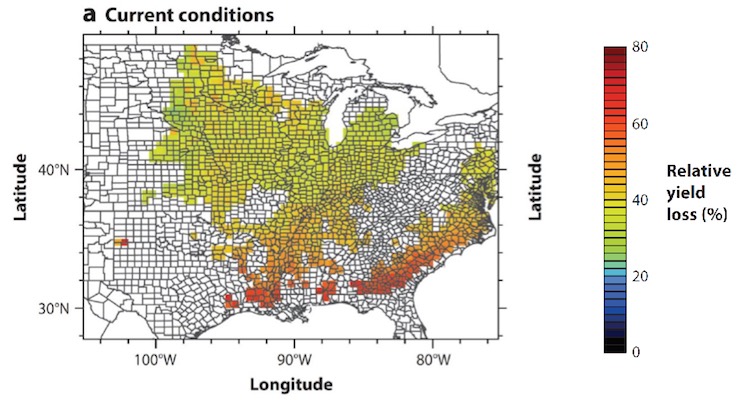

Modeling can be used to understand plant performance under dynamic conditions. Shown is how much crop yield is decreased by a photorespiration; a byproduct of photosynthesis and an area of special interest to the Walker lab. Taken from Walker, VanLoocke, Bernacchi and Ort (2016) The costs of photorespiration to food production now and in the future. Annual review of plant biology (67).

We have three main projects in the lab:

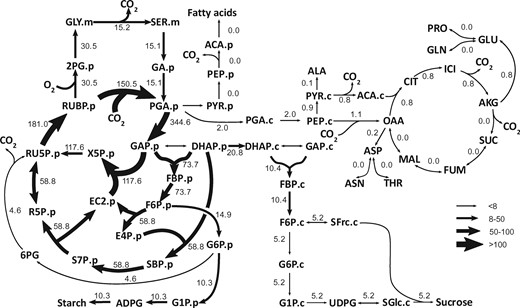

By using 13C as a label we are able to reconstruct metabolic fluxes and tie them into leaf-level gas exchange. In this flux map we determined that carbon dioxide release does not occur at large rates from the TCA cycle in the light, an important finding for understanding the carbon balance of plants. Taken from Yuan Xu, Xinyu Fu, Thomas D Sharkey, Yair Shachar-Hill, and Berkley J Walker (2021) The metabolic origins of non-photorespiratory CO2 release during photosynthesis: a metabolic flux analysis. Plant Physiology (186).

How does photorespiratory flux interact with other metabolisms?

Photorespiration is the second largest metabolic flux of carbon in an illuminated leaf and occurs when rubisco, the initial enzyme of carbon fixation, binds with oxygen instead of carbon dioxide and produces a molecule that must be recycled. Photorespiration recycles this molecule into Calvin-Benson cycle intermediates at the great cost of carbon dioxide and energy. Given its outsized role in central metabolism, we are interested in how photorespiration interacts with other aspects of central metabolism like nitrogen metabolism and one-carbon metabolism. To do this we use a variety of flux approaches, ranging from leaf-level measurements of photosynthesis to formal metabolic flux analysis using 13C labeled carbon dioxide.

How does photorespiration beat the heat?

Understanding the mechanisms of carbon dioxide release during photorespiration is critical for predicting plant responses to climate change and potentially engineering plants with improved carbon assimilation and productivity. While there has been a lot of focus on the response of rubisco oxygenation to increased temperature, less is known about how downstream photorespiration responds, or if its response is always optimal to minimize excess carbon dioxide release. To investigate this, we are looking at how photorespiration adapts and acclimates to different conditions. We are also building a well-parameterized reaction-kinetic model of photorespiration to understand if it always behaves optimally and if there might be any room for improvement. The results of this project will reach across disciplinary boundaries with the strong potential to improve earth-system models of carbon cycling and to identify key traits for adapting photosynthesis to real-world growing conditions.

What is the physiology of bioenergy crops?

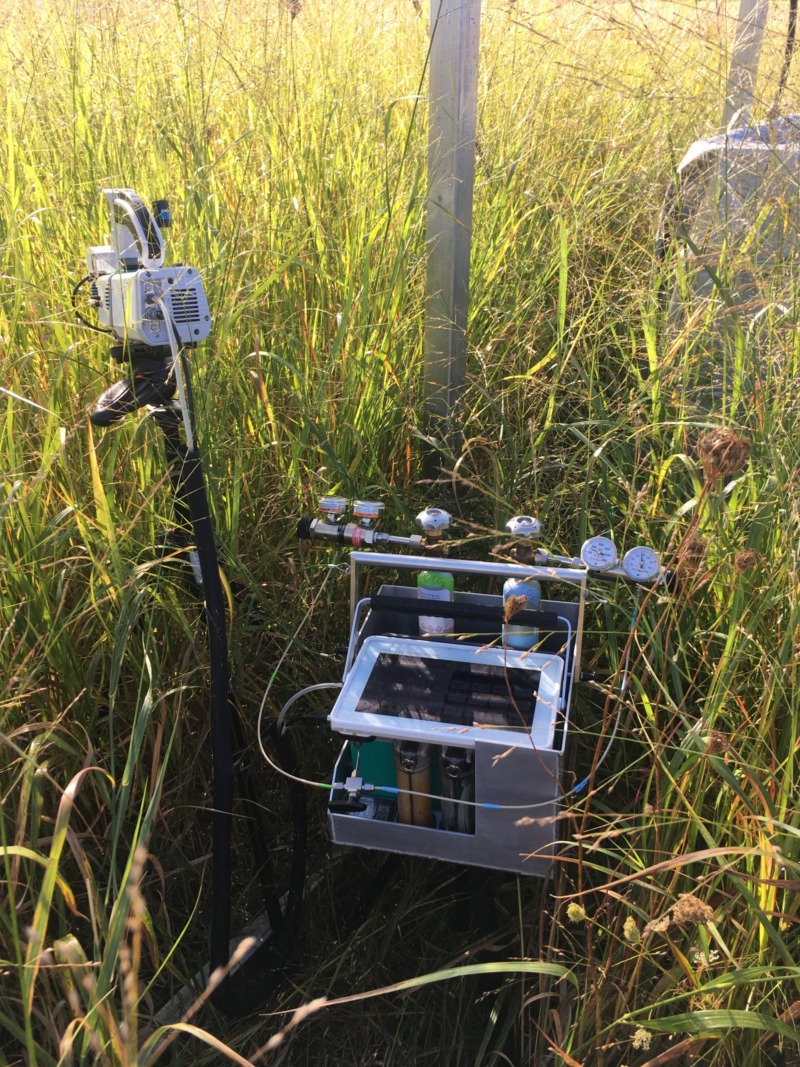

Sustainable bioenergy systems require a shift from annual crops, like corn and soybean, to perennial crops that do not need to be replanted every year. These perennial crops avoid the annual soil disturbance that results in carbon dioxide release and a “carbon debt” that can take years to repay before the biofuel is net carbon negative. These perennial crops, like switchgrass, have unique physiology and high resilience to environmental stresses. In out lab we study the physiology of switchgrass to understand how it is able to maintain productivity under drought and other stresses to both further improve its productivity and learn lessons for potentially improving other crops.

Research capabilities

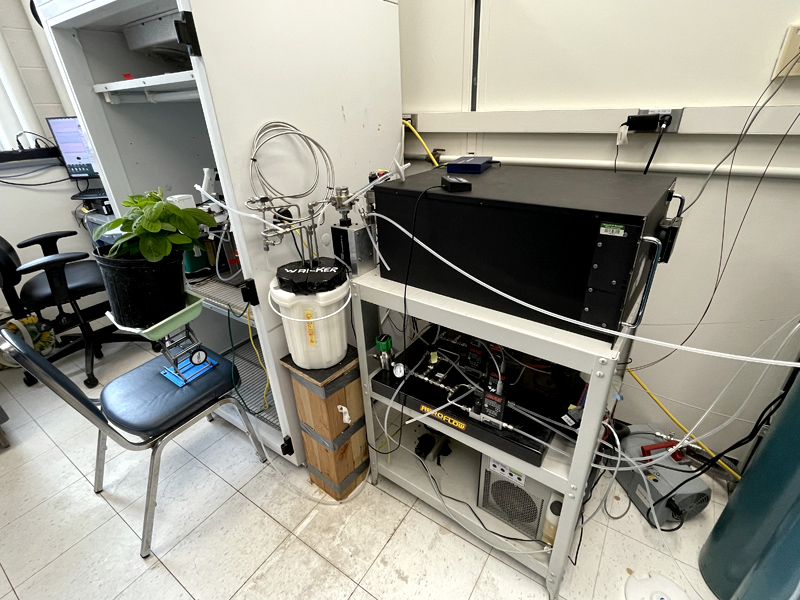

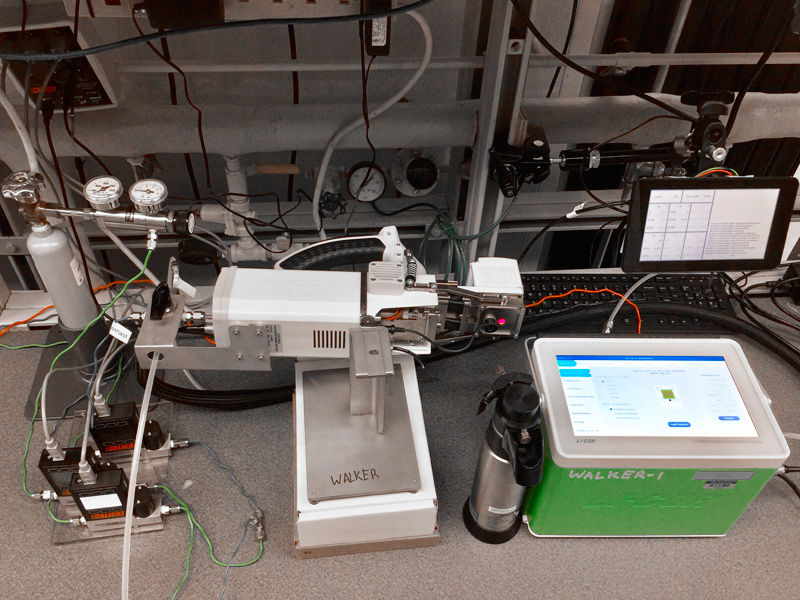

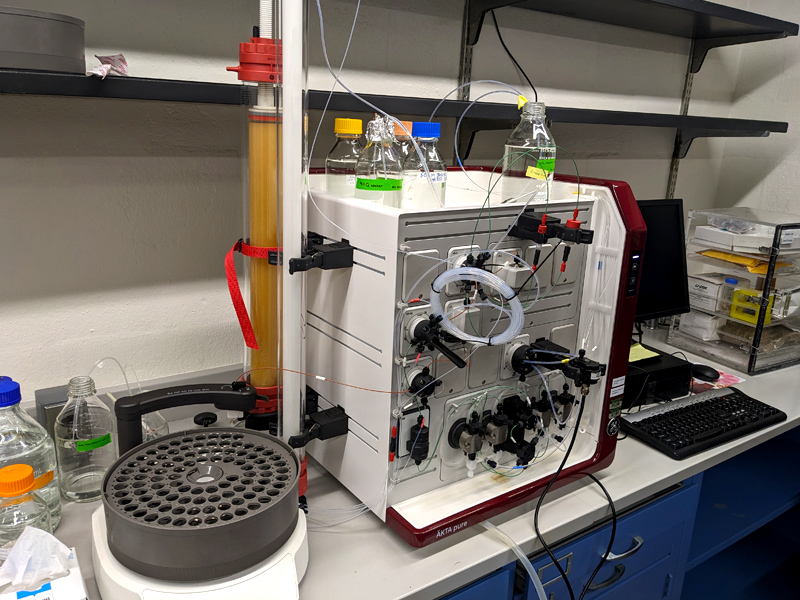

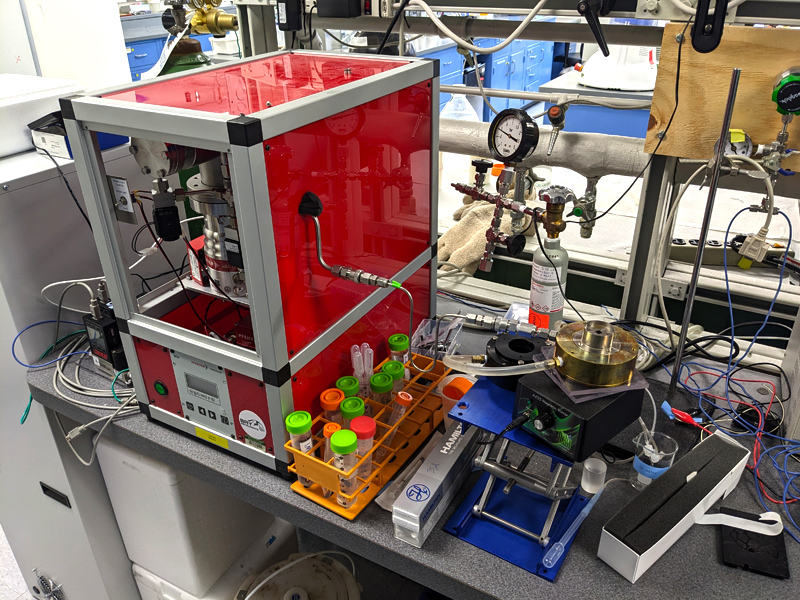

The Walker lab has a full complement of commercial and customized instrumentation to enable the research in the lab.

Fleet of LI-COR 6800’s for making lab and field-based measurements of CO2 exchange, H2O exchange, and chlorophyll fluorescence

Aerodyne Tunable Infrared Laser Direct Absorption Spectroscopy (TILDAS) for online measurements of 13CO2 isotope discrimination

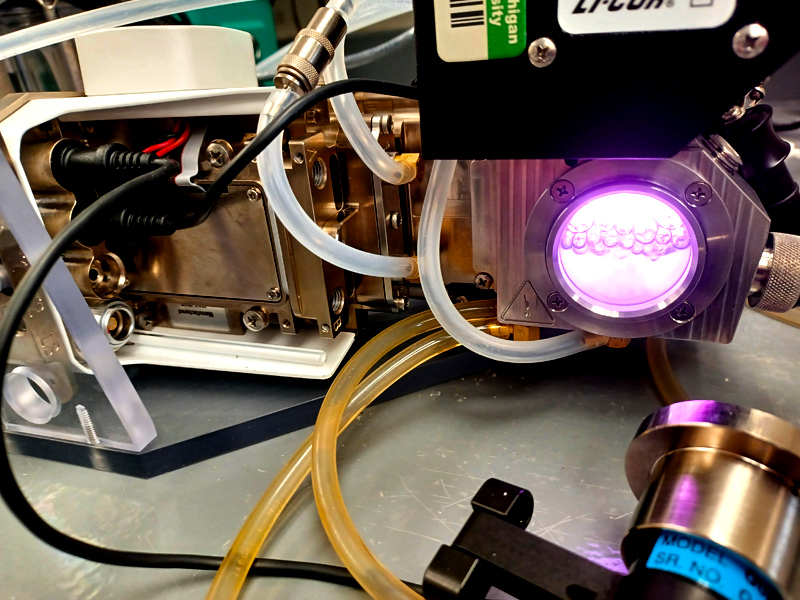

Dynamic Environmental Photosynthetic Imager (on loan from the Kramer Lab, thanks!) with capacity to measure under any O2 or CO2 condition desired

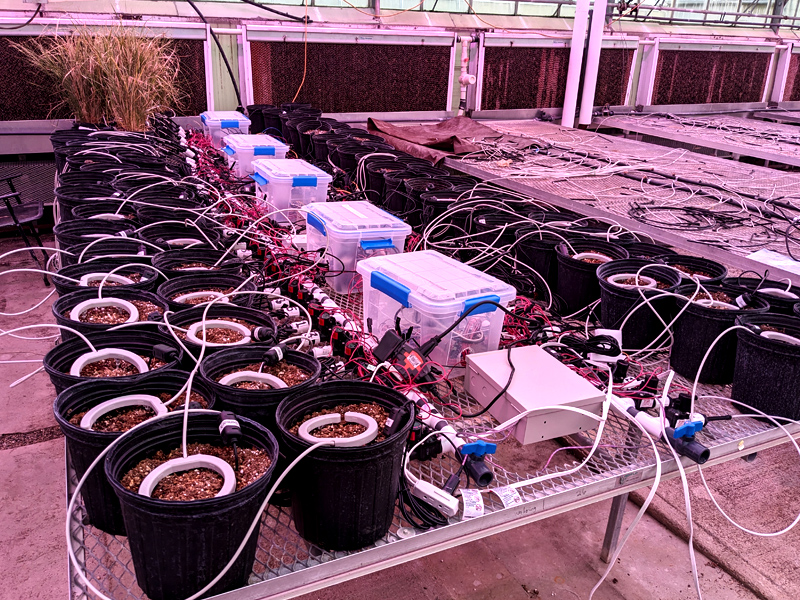

Rapid labeling and quench system for performing 13CO2-based metabolic flux analysis experiments

Field-deployable labeling and quench system for performing 13CO2-based metabolic flux analysis experiments

ӒKTA pure chromatography system for protein purification

A Pfeiffer-based quadrupole Bay Instruments Membrane inlet mass spectrometer for measuring exchange fluxes of isotopically enriched 13CO2 and 18O2

LI-COR 6800-18 aquatic chamber for measuring CO2 exchange in liquid-phase systems